Cool stuff and UX resources

The average internet user performed 33 searches in June of 2004. Are you above average?

A recent memo released by the PEW/Internet and American Life Project reports that the use of search engines ranks second only to email as the most popular activity on-line. On any given day, they continue, roughly half of the 64 million American adults who are on-line will use a search engine.

Historically, reports of increasing popularity of specific search engines has lead researchers to postulate that users may soon begin to adopt search as a primary strategy for navigation. For instance, Nielsen (2000) postulated that ½ of users are "search dominant." This assertion, in combination with recognition that navigation structures are often poorly designed, resulted in a flurry of design guidelines around best practices for search engine design and implementation. The theory was that half the world wants to use search, anyway. When the other half encountered unusable browse navigation, they would switch to search.

Human decision making, however, is rarely that transparent or logical.

Recent research suggests that users' decisions to search or browse depends as much on the site as on the users' disposition toward a given navigation strategy. For instance, Katz and Byrne (2004) report that navigation strategies selection on on-line shopping sites depends on menu breadth and information scent. Information scent derives from information foraging theory to describe how much and how confidently a user can predict remote information based on the design and labels used in an information structure (Pirolli and Card, 1995). Clear labels provide good scent. Breadth refers to the number of navigation options a user has on a given level of a site. Greater breadth means more choices.

Katz and Byrne found that increasing either scent or breadth significantly increased users tendency to browse: participants searched on less than 10% of trials for sites with large menus presenting concretely labeled categories.

Critically, Katz and Bryne also show that users tend to browse even in sub-optimal menu conditions: Participants chose browse over half of the time (~60%) even on sites with limited menus with ambiguously labeled categories.

Please don't beam me up, Scotty...

To further describe how and when users decide to search versus browse, Teevan, Alvarado, Ackerman and Karger (2004) report a modified diary study of motivated information seeking across email, files and the Web. They conducted burst interviews with each of the participants at two unspecified interruption points per day for 5 consecutive days. The "interviews" were simple 5 minute debriefs in which the researchers asked the participant to describe what s/he had recently "looked at" or "looked for" in their email, files or on the Web. The burst interviews were supplemented by direct observation and longer semi-structured interviews to explore their information patterns.

Given the participants' advanced computer experience and familiarity with complex information spaces and sophisticated search tools (The participants were MIT Computer Science Graduate Students), Teevan and colleagues were surprised to find that their participants used key-word searches in only 39% of their searches – despite the fact that they almost always knew key details of the information they needed up front.

Based on their findings, Teevan and team describe two strategies for information navigation: Teleporting and Orienteering.

Teleporting occurs when a person jumps directly to the information they are seeking.

Orienteering consists of narrowing the search space through a series of steps (e.g., selecting links) based on prior and contextual information to hone in on the target. Most often, participants took an initial "large" step to the vicinity or information source (e.g., typing the URL bonjourquebec.com to find information about Quebec City) and then refined the search space further through smaller steps based on local exploration.

Teevan, et.al., argue that orienteering provides three benefits for the user over teleporting:

- Orienteering is less cognitively demanding. It does not require discrete articulation of the searched-for item at the onset of the search. It allows users to rely on habit to get to the information target space, effectively reducing the search space.

- Orienteering provides the user a greater sense of control and location.

- Small, incremental steps in orienteering provide additional context for interpreting results.

In their study, Teevan and colleagues observed significantly more orienteering than teleporting behavior. Three additional interesting observations emerged. First, participants in their study consciously chose not to teleport, even when teleporting appeared viable. Second, participants tended not to use keyword searching. Third, on some occasions when participants employed keyword search, it was used as a tactic within orienteering. That is, at least one participant used iterative keyword searches to incrementally narrow the search space in small steps.

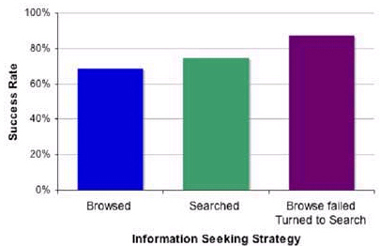

Figure 1: Relative success rates for browse versus search navigation on a US government medical information site

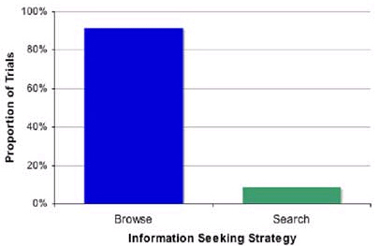

Figure 2: Participants typically tried browse first even when search worked better

Old dogs prefer old tricks

So, the prevailing research suggests that users tend to prefer to take small, incremental steps through the information space to find relevant information. They tend to browse – even when they know precisely what they are looking for from the onset.

But we need to go back to the earlier question. Do people who are browsers switch strategies when they realize the Web is broken?

What happens when browsing fails and search works? Do users switch strategies locally?

Straub and Valdes (in preparation) report a pilot study of user navigation preferences in which participants completed specific information-seeking tasks on a US government medical information site running a well-indexed Google site-tool.

As shown in Figure 1, participants found the desired information numerically more often when they searched than when they browsed (Success Rates: Browse: 69%; Search: 75%; Browse failed, tried Search: 88%).

However, despite the fact that search yielded better results, users tended to return to browse on the next information task. As can be seen in Figure 2, over the course of the study participants took a browse-first approach on 91% of the trials.

In this study, even though search yielded nominally better outcomes, users returned loyally to browse for (subsequent) tasks.

Conclusion

What does this mean for design? Taken together, these findings suggest that although search engines may become more usable, it is highly unlikely that they will become the primary means of navigation.

References

Fallows, D and Rainie, L. (2004) The popularity and importance of search engines. PEW Internet and American Life Project Memo.

Katz, M. A. and Byrne, M. D. (2003). Effects of Scent and Breadth on Use of Site-specific Search on E-Commerce Web Sites. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 10(3) pp 198-220.

Pirolli, P, and Card, S. (1995). Information foraging in information access environments. Proceedings of ACM CHI 95. pp. 51-58.

Scanlon, T. (2000) On-site searching and scent. User Interface Engineering, Inc. Report. North Andover, MA.

Teevan, J., Alvarado, C., Ackerman, M. and Karger, D. (2004). The perfect Search Engine is not Enough: A Study of Orienteering Behavior in Directed Search. Proceedings of ACM CHI 2004, pp. 415-4422.

Message from the CEO, Dr. Eric Schaffer — The Pragmatic Ergonomist

Leave a comment here

Subscribe

Sign up to get our Newsletter delivered straight to your inbox