Introduction

We’ve got a usability test day coming up and we’ve planned on five participants. That’s the magic number to find most of the important problems, right?

During design, UX teams do formative testing – focusing on qualitative data and learning enough to move the design forward. But how many participants are needed to have confidence in the test results? That debate’s been going for a quarter-century.

Your design team can learn a lot from just a few usability participants, but only if you are prepared to act on those results, redesign, and retest. Also, not all critical problems are found easily with just a few people – so if you’re working on a complex system or one where lives are at stake, you’ll want to be more thorough.

Moreover, there’s a statistical approach to estimating whether a few participants are enough, or whether it takes more of them to discover usability problems. Jeff Sauro and James Lewis (2012) discuss usability problem discoverability, do sample size calculations, and helpfully summarize them in table form. We’ll share those here.

Finally, we’ll review factors to consider in assessing whether your design has problems that are easier or harder to discover.

The magic number 5?

Five users can be enough – if problems are somewhat easy to discover, and if you don’t expect to find all problems with just one test.

Problem discoverability (here, p) is the likelihood that at least one participant will encounter the problem during usability testing. Nielsen and Landauer (1993; see also Nielsen, 2012) found on average p=0.31 for the set of projects studied. Based on that, 5 users would be expected to find 85% of the usability problems available for discovery in that test iteration.

Similarly, Virzi (1992) created a model based on other usability projects, finding p between 0.32 and 0.42. Therefore, 80% of the usability problems in a test could be detected with 4 or 5 participants.

And so a UX guideline was born. For the best return on investment, test with 5 users, find the majority of problems, fix them, and retest. For wider coverage, vary the types of users and the tasks tested in subsequent iterations.

Problem discoverability and sample size

But the “5-user assumption” doesn’t hold up consistently. Faulkner (2003), using yet another benchmark task, found that although tests with 5 users revealed an average of 85% of usability problems, percentages ranged from nearly 100% down to only 55%. Groups of 10 did much better, finding 95% of the problems with a lower bound of 82%.

Perfetti and Landesman (2001) tested an online music site. After 5 users, they’d found only 35% of all usability issues. After 18 users, they still were discovering serious issues and had uncovered less than half of the 600 estimated problems. Spool and Schroeder (2001) also reported a large-scale website evaluation for which 5 participants were nowhere near discovering 85% of the problems.

Why the discrepancy? Blame low problem discoverability, p.

First, large and complex systems can’t be covered completely during a 1-hour usability test. We often just have users going through a few important scenarios, out of dozens, encountering a handful of tasks in each scenario.

Second, even once we’ve focused on important scenarios, some are relatively unstructured. That lack of structure contributes to low p. When participants have more variety of paths to an end goal, they have a greater number of problems available for discovery along the way, so any given problem is less likely to be found.

Using problem discoverability to plan sample size

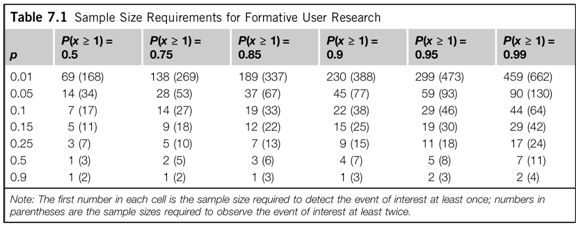

Sauro and Lewis (2012) provide tables to help researchers plan sample size with problem discoverability in mind. Table 7.1 (p. 146) shows sample size requirements as a function of problem occurrence probability, p, and the likelihood of detecting the problem at least once, P(x≥1).

For example, if you were interested in slightly harder-to-find problems (p=0.15) and wanted to be 85% sure of finding them, you’d need to have 12 participants in the test. Notice how quickly sample sizes grow for the most difficult-to-find problems and the greatest certainty of finding them!

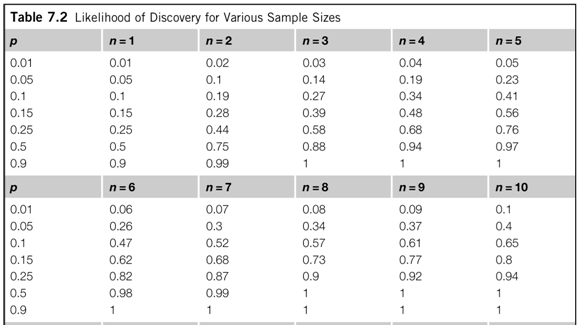

Another way to look at the tradeoffs is with Table 7.2 (p. 147, excerpt below). For a given sample size, how well can you do at detecting different kinds of problems? With 10 participants, you can expect to find nearly all of the moderately frequently occurring problems (p=0.25, 94%), less than half of more rare problems (p=0.05, 40%), and so on.

Note that if you expect your problems in general to be harder to find – as for Perfetti and Landesman – you’ll want more participants in your studies.

But how discoverable are your design’s problems?

Sauro and Lewis (p. 153) give a method for bootstrapping an estimate of p: test with two participants, note the number and overlap in discovered problems, adjust the estimated sample size, then repeat after four participants.

But pragmatically? On a design project we’re typically using “t-shirt sizing” for test sample sizes: small (~5), medium (~10), or large (~25). For formative testing, where we want to learn, iterate, and keep the design moving forward, that typically means choosing between a small and medium sample size for any given test.

What factors increase discoverability and make small sample size work? Sauro and Lewis list several, and our experience suggests others:

- Expert test observers.

- Multiple test observers.

- New products with newly designed interfaces, rather than more matured and refined designs.

- Less-skilled participants; more knowledgeable participants can work around known problems.

- A homogeneous (but still representative) set of participants.

- Structured tasks, where there’s a path along which problems are discovered.

- Coverage. For a larger design, include a wide-ranging set of tasks, both simple and complex.

- Alternatively, focus a small test on just one design aspect, iterate quickly, and move to the next issue (see Schrag, 2006).

Small tests: Doing them RITE

Formative testing is worthless if the design doesn’t change. Whether the method is called discount, Lean, or Agile, small tests are intended to deliver design guidance in a timely way throughout development.

But do decision-makers agree that the problems found are real? Are resources allocated to fix the problems? Can teams be sure that the proposed solutions will work? If not, it doesn’t matter how cheaply you’ve done the test; it has zero return on investment.

Medlock and colleagues at Microsoft (2005) addressed process issues head-on with their Rapid Iterative Testing and Evaluation (RITE) method. Read the full article for their clear description of the depth of involvement and speed of response required from the development organization. Rapid small-n iterative testing is a full-contact team sport.

Focusing on testing methodology itself, Medlock et al. listed specific requirements for RITE, including:

- Firm agreement on tasks all participants must be able to perform.

- Ability of the usability engineer to assess whether a problem observed once is “reasonably likely to be a problem for other people,” which requires domain and problem experience.

- Quick prioritization of issues according to obviousness of cause and solution. Don’t rush to make all changes quickly; poorly solved issues can “break” other parts of the user experience.

- Incorporating fixes as soon as possible, even if after just one participant.

- Commitment to run follow-up tests with as many participants as needed to confirm the fixes.

Found a problem! So is it real?

One of our five participants had a problem. Should we fix it? Or is it an idiosyncrasy, a glitch, a false positive?

Usability expertise plays an important role in weighing evidence and assessing the root cause of the problem. Sauro and Lewis note the benefits of expert (and multiple) observers. The RITE method relies on a usability specialist who is also expert in the domain.

The more subtle the problem, the more the team needs someone who can persuasively say, “Based on what I know of human performance, and of users’ behavior with similar interfaces, this really is (or isn’t) an issue.”

Of course, given small and relatively inexpensive tests, the team can fix obvious problems and then collect more data on edge cases in the next iteration.

Medium and large tests: Risk management

Small iterative usability tests reduce certain kinds of risks: timeliness of feedback, impact of feedback, and time to market. In particular, small tests early in the design process can help the team converge more quickly on usable designs.

But when lives are at stake, there are other risks to consider. Tests must be designed to find uncommon but critical usability problems. In Sauro and Lewis’ analysis, this means consulting columns of the sample size table where the likelihood of detecting problems at least once, P(x≥1), is large, and sample sizes increase.

For example, take medical devices. At the end of product development it’s important to confirm that the device is safe and effective for human use. That is a summative or validation test, and requires about 25 participants per user group (FDA, 2011).

Even during formative testing sample sizes closer to 10 are more common (Wiklund, 2007). We know one researcher who routinely tests 15 or 20 participants per group. This mitigates two types of risks: not only the use-safety risk to the human user, but also the business risk of missing critical problems, failing validation, and having to wait months to re-test and resubmit the product for regulatory approval!

Those of us developing unregulated systems and products might still choose larger sample sizes of 8-10. The larger number may be more persuasive to stakeholders. It may allow us to handle more variability within each user group. Or it may be a small incremental cost to the project (Nielsen, 2012).

If you work for a centralized UX group that isn’t integrated as tightly with a given development team as an iterative discount method requires – or you’re a consultant hired only as needed – you need to get the most from that usability testing opportunity. Consider using a larger sample size.

Small, medium, large: What size of test fits you?

The “magic” number 5 is not magic at all. It depends on assumptions about problem discoverability and has implications for design process and business risk. Assess these three factors to determine whether five participants is enough for you:

- Are problems hard to find? Are the participants expert, the usability engineer less familiar with the domain, or the system complex and flexible?

- Is your organization equipped to do iterative small-n tests? Are you set up for ongoing recruitment-and-test operations, committed to iteration, and able to deliver software changes rapidly?

- What are the safety and business risks of missing uncommon problems in your design?

At the very least, make sure to assess how variable your participants are. If they differ significantly in expertise or in typical tasks, recruit at least five participants per user group.

Happy testing!

References

- Faulkner, L. (2003). Beyond the five-user assumption: Benefits of increased sample sizes in usability testing. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 35(3), 379-383.

- FDA (2011, June 22). Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff – Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Optimize Medical Device Design. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/.

- Medlock, M.C., Wixon, D., McGee, M., and Welsh, D. (2005). The rapid iterative test and evaluation method: Better products in less time. In: Bias, R.G. and Mayhew, D.J. (Eds.), Cost-Justifying Usability: An Update for the Internet Age. Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands. 489–517.

- Nielsen, J. (2012, June 4). How many test users in a usability study? Retrieved from http://www.nngroup.com.

- Nielsen, J. & Landauer, T.K. (1993). A mathematical model of the finding of usability problems. Proceedings of ACM INTERCHI’93 Conference (Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24-29 April 1993), 206-213.

- Perfetti, C., & Landesman, L. (2001, June 18). Eight is not enough. Retrieved from http://uie.com.

- Sauro, J. & Lewis, J. R (2012). Quantifying the user experience: Practical statistics for user research. Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Schrag, J. (2006, June 15). Using formative usability testing as a fast UI design tool. Retrieved from http://dux.typepad.com.

- Spool, J., & Schroeder, W. (2001). Testing web sites: Five users is nowhere near enough. In CHI 2001 Extended Abstracts. New York: ACM Press, 285-286.

- Virzi, R.A. (1992). Redefining the test phase of usability evaluation: How many subjects is enough? Human Factors, 34, 457-468.

- Wiklund, M. (2007, October 1). Usability testing: Validating user interface design. Retrieved from http://mddionline.com.

Message from the CEO, Dr. Eric Schaffer – The Pragmatic Ergonomist

Leave a comment here

Subscribe

Sign up to get our Newsletter delivered straight to your inbox