- About us

- Contact us: +1.641.472.4480, hfi@humanfactors.com

Cool stuff and UX resources

The average internet user performed 33 searches in June of 2004. Are you above average?

A recent memo released by the PEW/Internet and American Life Project reports that the use of search engines ranks second only to email as the most popular activity on-line. On any given day, they continue, roughly half of the 64 million American adults who are on-line will use a search engine.

Historically, reports of increasing popularity of specific search engines has lead researchers to postulate that users may soon begin to adopt search as a primary strategy for navigation. For instance, Nielsen (2000) postulated that ¬Ĺ of users are "search dominant." This assertion, in combination with recognition that navigation structures are often poorly designed, resulted in a flurry of design guidelines around best practices for search engine design and implementation. The theory was that half the world wants to use search, anyway. When the other half encountered unusable browse navigation, they would switch to search.

Human decision making, however, is rarely that transparent or logical.

Recent research suggests that users' decisions to search or browse depends as much on the site as on the users' disposition toward a given navigation strategy. For instance, Katz and Byrne (2004) report that navigation strategies selection on on-line shopping sites depends on menu breadth and information scent. Information scent derives from information foraging theory to describe how much and how confidently a user can predict remote information based on the design and labels used in an information structure (Pirolli and Card, 1995). Clear labels provide good scent. Breadth refers to the number of navigation options a user has on a given level of a site. Greater breadth means more choices.

Katz and Byrne found that increasing either scent or breadth significantly increased users tendency to browse: participants searched on less than 10% of trials for sites with large menus presenting concretely labeled categories.

Critically, Katz and Bryne also show that users tend to browse even in sub-optimal menu conditions: Participants chose browse over half of the time (~60%) even on sites with limited menus with ambiguously labeled categories.

Please don't beam me up, Scotty...

To further describe how and when users decide to search versus browse, Teevan, Alvarado, Ackerman and Karger (2004) report a modified diary study of motivated information seeking across email, files and the Web. They conducted burst interviews with each of the participants at two unspecified interruption points per day for 5 consecutive days. The "interviews" were simple 5 minute debriefs in which the researchers asked the participant to describe what s/he had recently "looked at" or "looked for" in their email, files or on the Web. The burst interviews were supplemented by direct observation and longer semi-structured interviews to explore their information patterns.

Given the participants' advanced computer experience and familiarity with complex information spaces and sophisticated search tools (The participants were MIT Computer Science Graduate Students), Teevan and colleagues were surprised to find that their participants used key-word searches in only 39% of their searches ‚Äď despite the fact that they almost always knew key details of the information they needed up front.

Based on their findings, Teevan and team describe two strategies for information navigation: Teleporting and Orienteering.

Teleporting occurs when a person jumps directly to the information they are seeking.

Orienteering consists of narrowing the search space through a series of steps (e.g., selecting links) based on prior and contextual information to hone in on the target. Most often, participants took an initial "large" step to the vicinity or information source (e.g., typing the URL bonjourquebec.com to find information about Quebec City) and then refined the search space further through smaller steps based on local exploration.

Teevan, et.al., argue that orienteering provides three benefits for the user over teleporting:

- Orienteering is less cognitively demanding. It does not require discrete articulation of the searched-for item at the onset of the search. It allows users to rely on habit to get to the information target space, effectively reducing the search space.

- Orienteering provides the user a greater sense of control and location.

- Small, incremental steps in orienteering provide additional context for interpreting results.

In their study, Teevan and colleagues observed significantly more orienteering than teleporting behavior. Three additional interesting observations emerged. First, participants in their study consciously chose not to teleport, even when teleporting appeared viable. Second, participants tended not to use keyword searching. Third, on some occasions when participants employed keyword search, it was used as a tactic within orienteering. That is, at least one participant used iterative keyword searches to incrementally narrow the search space in small steps.

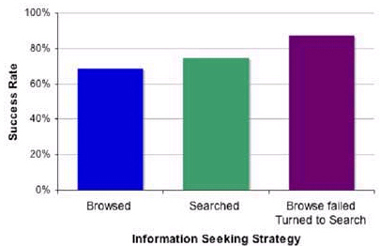

Figure 1: Relative success rates for browse versus search navigation on a US government medical information site

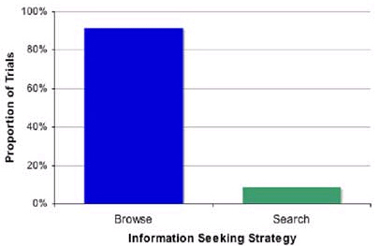

Figure 2: Participants typically tried browse first even when search worked better

Old dogs prefer old tricks

So, the prevailing research suggests that users tend to prefer to take small, incremental steps through the information space to find relevant information. They tend to browse ‚Äď even when they know precisely what they are looking for from the onset.

But we need to go back to the earlier question. Do people who are browsers switch strategies when they realize the Web is broken?

What happens when browsing fails and search works? Do users switch strategies locally?

Straub and Valdes (in preparation) report a pilot study of user navigation preferences in which participants completed specific information-seeking tasks on a US government medical information site running a well-indexed Google site-tool.

As shown in Figure 1, participants found the desired information numerically more often when they searched than when they browsed (Success Rates: Browse: 69%; Search: 75%; Browse failed, tried Search: 88%).

However, despite the fact that search yielded better results, users tended to return to browse on the next information task. As can be seen in Figure 2, over the course of the study participants took a browse-first approach on 91% of the trials.

In this study, even though search yielded nominally better outcomes, users returned loyally to browse for (subsequent) tasks.

Conclusion

What does this mean for design? Taken together, these findings suggest that although search engines may become more usable, it is highly unlikely that they will become the primary means of navigation.

References

Fallows, D and Rainie, L. (2004) The popularity and importance of search engines. PEW Internet and American Life Project Memo.

Katz, M. A. and Byrne, M. D. (2003). Effects of Scent and Breadth on Use of Site-specific Search on E-Commerce Web Sites. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 10(3) pp 198-220.

Pirolli, P, and Card, S. (1995). Information foraging in information access environments. Proceedings of ACM CHI 95. pp. 51-58.

Scanlon, T. (2000) On-site searching and scent. User Interface Engineering, Inc. Report. North Andover, MA.

Teevan, J., Alvarado, C., Ackerman, M. and Karger, D. (2004). The perfect Search Engine is not Enough: A Study of Orienteering Behavior in Directed Search. Proceedings of ACM CHI 2004, pp. 415-4422.

Message from the CEO, Dr. Eric Schaffer ‚ÄĒ The Pragmatic Ergonomist

Leave a comment here

Subscribe

Sign up to get our Newsletter delivered straight to your inbox

Privacy policy

Reviewed: 18 Mar 2014

This Privacy Policy governs the manner in which Human Factors International, Inc., an Iowa corporation (‚ÄúHFI‚ÄĚ) collects, uses, maintains and discloses information collected from users (each, a ‚ÄúUser‚ÄĚ) of its humanfactors.com website and any derivative or affiliated websites on which this Privacy Policy is posted (collectively, the ‚ÄúWebsite‚ÄĚ). HFI reserves the right, at its discretion, to change, modify, add or remove portions of this Privacy Policy at any time by posting such changes to this page. You understand that you have the affirmative obligation to check this Privacy Policy periodically for changes, and you hereby agree to periodically review this Privacy Policy for such changes. The continued use of the Website following the posting of changes to this Privacy Policy constitutes an acceptance of those changes.

Cookies

HFI may use ‚Äúcookies‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúweb beacons‚ÄĚ to track how Users use the Website. A cookie is a piece of software that a web server can store on Users‚Äô PCs and use to identify Users should they visit the Website again. Users may adjust their web browser software if they do not wish to accept cookies. To withdraw your consent after accepting a cookie, delete the cookie from your computer.

Privacy

HFI believes that every User should know how it utilizes the information collected from Users. The Website is not directed at children under 13 years of age, and HFI does not knowingly collect personally identifiable information from children under 13 years of age online. Please note that the Website may contain links to other websites. These linked sites may not be operated or controlled by HFI. HFI is not responsible for the privacy practices of these or any other websites, and you access these websites entirely at your own risk. HFI recommends that you review the privacy practices of any other websites that you choose to visit.

HFI is based, and this website is hosted, in the United States of America. If User is from the European Union or other regions of the world with laws governing data collection and use that may differ from U.S. law and User is registering an account on the Website, visiting the Website, purchasing products or services from HFI or the Website, or otherwise using the Website, please note that any personally identifiable information that User provides to HFI will be transferred to the United States. Any such personally identifiable information provided will be processed and stored in the United States by HFI or a service provider acting on its behalf. By providing your personally identifiable information, User hereby specifically and expressly consents to such transfer and processing and the uses and disclosures set forth herein.

In the course of its business, HFI may perform expert reviews, usability testing, and other consulting work where personal privacy is a concern. HFI believes in the importance of protecting personal information, and may use measures to provide this protection, including, but not limited to, using consent forms for participants or ‚Äúdummy‚ÄĚ test data.

The Information HFI Collects

Users browsing the Website without registering an account or affirmatively providing personally identifiable information to HFI do so anonymously. Otherwise, HFI may collect personally identifiable information from Users in a variety of ways. Personally identifiable information may include, without limitation, (i)contact data (such as a User’s name, mailing and e-mail addresses, and phone number); (ii)demographic data (such as a User’s zip code, age and income); (iii) financial information collected to process purchases made from HFI via the Website or otherwise (such as credit card, debit card or other payment information); (iv) other information requested during the account registration process; and (v) other information requested by our service vendors in order to provide their services. If a User communicates with HFI by e-mail or otherwise, posts messages to any forums, completes online forms, surveys or entries or otherwise interacts with or uses the features on the Website, any information provided in such communications may be collected by HFI. HFI may also collect information about how Users use the Website, for example, by tracking the number of unique views received by the pages of the Website, or the domains and IP addresses from which Users originate. While not all of the information that HFI collects from Users is personally identifiable, it may be associated with personally identifiable information that Users provide HFI through the Website or otherwise. HFI may provide ways that the User can opt out of receiving certain information from HFI. If the User opts out of certain services, User information may still be collected for those services to which the User elects to subscribe. For those elected services, this Privacy Policy will apply.

How HFI Uses Information

HFI may use personally identifiable information collected through the Website for the specific purposes for which the information was collected, to process purchases and sales of products or services offered via the Website if any, to contact Users regarding products and services offered by HFI, its parent, subsidiary and other related companies in order to otherwise to enhance Users’ experience with HFI. HFI may also use information collected through the Website for research regarding the effectiveness of the Website and the business planning, marketing, advertising and sales efforts of HFI. HFI does not sell any User information under any circumstances.

Disclosure of Information

HFI may disclose personally identifiable information collected from Users to its parent, subsidiary and other related companies to use the information for the purposes outlined above, as necessary to provide the services offered by HFI and to provide the Website itself, and for the specific purposes for which the information was collected. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information at the request of law enforcement or governmental agencies or in response to subpoenas, court orders or other legal process, to establish, protect or exercise HFI’s legal or other rights or to defend against a legal claim or as otherwise required or allowed by law. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information in order to protect the rights, property or safety of a User or any other person. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information to investigate or prevent a violation by User of any contractual or other relationship with HFI or the perpetration of any illegal or harmful activity. HFI may also disclose aggregate, anonymous data based on information collected from Users to investors and potential partners. Finally, HFI may disclose or transfer personally identifiable information collected from Users in connection with or in contemplation of a sale of its assets or business or a merger, consolidation or other reorganization of its business.

Personal Information as Provided by User

If a User includes such User’s personally identifiable information as part of the User posting to the Website, such information may be made available to any parties using the Website. HFI does not edit or otherwise remove such information from User information before it is posted on the Website. If a User does not wish to have such User’s personally identifiable information made available in this manner, such User must remove any such information before posting. HFI is not liable for any damages caused or incurred due to personally identifiable information made available in the foregoing manners. For example, a User posts on an HFI-administered forum would be considered Personal Information as provided by User and subject to the terms of this section.

Security of Information

Information about Users that is maintained on HFI’s systems or those of its service providers is protected using industry standard security measures. However, no security measures are perfect or impenetrable, and HFI cannot guarantee that the information submitted to, maintained on or transmitted from its systems will be completely secure. HFI is not responsible for the circumvention of any privacy settings or security measures relating to the Website by any Users or third parties.

Correcting, Updating, Accessing or Removing Personal Information

If a User’s personally identifiable information changes, or if a User no longer desires to receive non-account specific information from HFI, HFI will endeavor to provide a way to correct, update and/or remove that User’s previously-provided personal data. This can be done by emailing a request to HFI at hfi@humanfactors.com. Additionally, you may request access to the personally identifiable information as collected by HFI by sending a request to HFI as set forth above. Please note that in certain circumstances, HFI may not be able to completely remove a User’s information from its systems. For example, HFI may retain a User’s personal information for legitimate business purposes, if it may be necessary to prevent fraud or future abuse, for account recovery purposes, if required by law or as retained in HFI’s data backup systems or cached or archived pages. All retained personally identifiable information will continue to be subject to the terms of the Privacy Policy to which the User has previously agreed.

Contacting HFI

If you have any questions or comments about this Privacy Policy, you may contact HFI via any of the following methods:

Human Factors International, Inc.

PO Box 2020

1680 highway 1, STE 3600

Fairfield IA 52556

hfi@humanfactors.com

(800) 242-4480

Terms and Conditions for Public Training Courses

Reviewed: 18 Mar 2014

Cancellation of Course by HFI

HFI reserves the right to cancel any course up to 14 (fourteen) days prior to the first day of the course. Registrants will be promptly notified and will receive a full refund or be transferred to the equivalent class of their choice within a 12-month period. HFI is not responsible for travel expenses or any costs that may be incurred as a result of cancellations.

Cancellation of Course by Participants (All regions except India)

$100 processing fee if cancelling within two weeks of course start date.

Cancellation / Transfer by Participants (India)

4 Pack + Exam registration: Rs. 10,000 per participant processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the course (4 Pack-CUA/CXA) registration before three weeks from the course start date. No refund or carry forward of the course fees if cancelling or transferring the course registration within three weeks before the course start date.

Cancellation / Transfer by Participants (Online Courses)

$100 processing fee if cancelling within two weeks of course start date. No cancellations or refunds less than two weeks prior to the first course start date.

Individual Modules: Rs. 3,000 per participant ‚Äėper module‚Äô processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the course (any Individual HFI course) registration before three weeks from the course start date. No refund or carry forward of the course fees if cancelling or transferring the course registration within three weeks before the course start date.

Exam: Rs. 3,000 per participant processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the pre agreed CUA/CXA exam date before three weeks from the examination date. No refund or carry forward of the exam fees if requesting/cancelling or transferring the CUA/CXA exam within three weeks before the examination date.

No Recording Permitted

There will be no audio or video recording allowed in class. Students who have any disability that might affect their performance in this class are encouraged to speak with the instructor at the beginning of the class.

Course Materials Copyright

The course and training materials and all other handouts provided by HFI during the course are published, copyrighted works proprietary and owned exclusively by HFI. The course participant does not acquire title nor ownership rights in any of these materials. Further the course participant agrees not to reproduce, modify, and/or convert to electronic format (i.e., softcopy) any of the materials received from or provided by HFI. The materials provided in the class are for the sole use of the class participant. HFI does not provide the materials in electronic format to the participants in public or onsite courses.