- About us

- Contact us: +1.641.472.4480, hfi@humanfactors.com

Cool stuff and UX resources

Mobile phones are often considered as powerful tools to persuade customers. The myriad of native hardware such as camera, accelerometer, magnetic sensor, GPS, light sensor, compass, etc., presents a unique opportunity to provide context specific experiences.

The fact that customers tend to carry their mobile phones continuously is also unique. Unlike any other device or accessory, mobile phones are even taken to washrooms! This provides a great opportunity to engage customers wherever they are. Last but not least is the emotional relationship that customers share with their devices.

Mobile phone users frown, kiss, shake, throw and even hurl profanities at their devices. This behavior highlights that mobile phones are not perceived as mindless machines but as social actors that play important roles in our lives.

Social responses to communication technologies theory (SRCT) strives to understand how technology/mobile phones are perceived as social actors. SRCT stresses that people apply social rules while interacting with computers. Computers can seem polite and can even shower flattery to persuade and change behavior.

Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber attempt to understand this behavior through a series of 5 experiments. The experiments strive to ask some key questions.

“What can we learn about human-computer interaction if we show that the human-computer relationship is fundamentally social? What can we predict and test if we assume that individuals are biased toward a social orientation; that when people sit down at a computer, they interact socially?”

The experiments were conducted with 180 computer-literate college students who volunteered to participate in various experiments involving a computer tutor. Each experiment lasted approximately 45 minutes. The participants were required to go through the following sessions:

- Practice session introducing the interface controls

- Tutoring session where participants were introduced to 25-30 facts

- Testing session where participants were required to answer 15 multiple choice questions

- Evaluation session where a computer evaluated the performance of the computerized tutoring session

- Assessment session where participants were asked to answer a questionnaire assessing the tutoring, testing and evaluation sessions

Will users apply politeness norms to computers?

This experiment was conducted with 33 participants. They used a single computer for the tutoring and testing sessions. The evaluation session was administered in three ways: via the same computer they were tutored on, via a different computer, or via pen and paper. The results of the experiment showed that participants who evaluated the same computer that they were tutored on were more polite. They indicated that the tutoring was more “friendly” and “competent.” It was also found that there weren’t significant differences in terms of evaluation while using a different computer or a pen and paper questionnaire. This confirms that participants related to “tutor computer” socially and ruled out the medium as an influencer.

Will users apply the notions of “self” and “other” to computers?

This experiment was conducted with 44 participants. Participants used 2 or 3 computers.

The first situation provided participants with the “same voice and box” condition. This meant that the evaluation session was conducted on the same computer and in the same voice as the tutoring session.

In the second situation participants were provided with the “different voice and box” condition. This meant that the evaluation session was conducted on a different computer and by a different voice than the tutoring session.

For each situation the computer either praised or criticized the tutoring session by describing 12 of 15 questions as positive or negative. The results of the experiment showed that participants believed that a distinct computer with a distinct voice was a different social actor.

In the situation when the tutoring session was praised by a different or same computer/voice, participants felt that praise by other computer/voice is more accurate and friendly than praise of self. In the case of criticism, participants felt the other computer/voice was less friendly but more intelligent than the one that praised. Participants also considered a praised tutoring better than a criticized tutoring.

On what basis do users distinguish computers as “self” or “other” ‚ÄĒ the voice or the box?

This experiment was conducted with 66 participants. This experiment was identical to the previous experiment except that there are 8 possible situations. These situations were formed through permutation of praise/criticism, same voice/different voice and same computer/different computer.

The results of the experiment showed that participants perceived different voices as different social actors. They also perceived the same voice across computers as the same social actor.

Will users apply gender stereotypes to computers?

This experiment was conducted with 48 participants, 24 male and 24 female. The testing session was given no voice while the tutoring and evaluation sessions were given either male or female voice. The topics for the tutoring and testing were love and relationships, mass media, and computers.

Participants perceived males who praise as more likable than females who praise. The evaluators with a male voice were considered more dominant, assertive, forceful, sympathetic and warmer than evaluators with a female voice.

Participants also perceived tutors with a female voice talking about love and relationships as more sophisticated and having chosen better, broader, and less-known facts than male tutors.

In situations where a different voice type was used for tutoring and evaluation, facts about love and relationships were seen as more informative, better-chosen, and broader than in the same-gender conditions.

If people do respond socially to computers, is it because they feel that they are interacting with the computer or with some other agent, such as the programmer?

This experiment was conducted with 33 participants, each using 2 computers. The protocol for this experiment required participants to experience the full cycle of tutoring/testing/evaluating twice. In the first cycle, the evaluations of tutoring were generally positive; in the second, they were generally negative. Tutoring and evaluation were conducted on one computer while testing was conducted on another.

There were three conditions created. In the first both experimenter and computer referred to the computer as “this computer” or “the computer.” In the second, the computer referred to itself as “I,” but the experimenter referred to it as “the computer.” In the third, the computer referred to itself as “I,” but the experimenter referred to it as “the programmer.”

The result of this experiment showed that in the first and second condition participants found the computer to be generally more capable, more likable, and easier to use than in the third condition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, across the five experiments, the following principles were derived:

- Social norms are applied to computers.

- Notions of “self’ and “other” are applied to computers.

- Voices are social actors.

- Notions of “self” and “other” are applied to voices.

- Computers are gendered social actors.

- Gender is an extremely powerful cue.

- Computer users respond socially to the computer itself.

- Computer users do not see the computer as a medium for social interaction with the programmer.

Though the above-summarized research was conducted based on desktop computers, the principles apply to mobile phones as well.

Another study that is more focused on mobile phones is “Intimate Self-Disclosure via Mobile Messaging.” This study explores SRCT in the context of mobile phones. Following are the hypotheses tested through the study:

- Participants will self-disclose more via mobile messaging in response to intimate questions coupled with the flattery and social norms strategies than via direct requests.

- Participants will self-disclose more via mobile messaging in response to intimate questions ostensibly from a human than from a computer.

- Participants’ self-disclosure via mobile messaging in response to intimate questions will be differentially affected by a human or computer sender that flatters them as compared to one that does not flatter them.

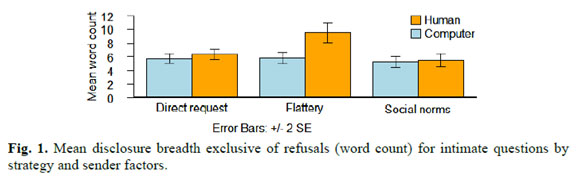

The study was conducted with 71 university students. The students received course credit or a $20 Amazon.com gift certificate as incentive and were told that the study was testing a new questionnaire system. All participants used their own mobile phones and service plans. The experiment conducted was based on permutation of sender and strategy. Sender could be of two types, human and computer. Strategy could be of three types, “direct request,” “flattery” and “social norms.”

Participants were asked to choose two periods, each about 2 days long, to participate. The periods were spaced one week apart. In each day, participants were required to choose an hour-long time slot to receive six to seven questions via text message. The first two questions sent to the participants in each period were low intimacy, and the remaining ten each period were high intimacy. An example of a high intimacy question could be “What has been the biggest disappointment in your life?”

In some cases the sender was referred to as “research assistant” while in others as “research computer.”¬† This was highlighted to the participants across two reminder emails and four welcome messages. In reality, all messages were sent by a computer.

In the “direct request” strategy, participants were only sent the question. In the “flattery” strategy, each question was accompanied by a compliment (e.g. “Nice reply!” or “You are better at texting than most.”). In the “social norms” strategy, the question was accompanied by a sentence stating the percentage (85-100%) of participants who had fully answered the question.

Breadth, or quantity, of disclosure is measured by word count. Responses which contained “no comment” were counted as 0 words.

The results of the experiment are summarized in the table and figure below.

The study showed that participants showed significantly more disclosure when flattery was provided by the ‘human’ sender than by the ‘computer’.¬† Different strategies did not elicit significantly different disclosure when the participants thought they were interacting with a ‘computer.’

It could be concluded that though people reciprocate with computers in self-disclosure, flattery is a more effective as a strategy for humans than computers. These results can be seen as inconsistent with predictions of SRCT.

Summary

Across the two contrasting studies talked about in this paper, it is evident people respond to computers/mobile phones as if they are social actors. This provides a tremendous opportunity to leverage mobile phones to persuade and induce behaviour change.

The point to keep in mind is that though there is a social response, it is not as much as human to human interaction. Technology/mobile phones have not arrived at the point where they could start to substitute human interaction. For now, they can be crude and rudimentary companions which humbly suggest and advise.

But the day is not far! As stated in Ray Kurzweil’s book The Spiritual Machine, the future of mankind would find a turning point when machines will start to surpass human intelligence and become a more than satisfactory substitute for human connection.

References

Computers are Social Actors

Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber

Department of Communication

Stanford University

Mobile Persuasion

20 Perspectives on the future of behaviour change

BJ Fogg & Dean Eckles

The Spiritual Machine

Ray Kurzweil

Intimate Self-Disclosure via Mobile Messaging:

Influence Strategies and Social Responses to Communication Technologies

Dean Eckles, Doug Wightman, Claire Carlson, Attapol Thamrongrattanarit,

Marcello Bastea-Forte, B.J. Fogg

Persuasive Technology Lab, Stanford University

Nokia Research Center, Palo Alto, CA

Message from the CEO, Dr. Eric Schaffer ‚ÄĒ The Pragmatic Ergonomist

Leave a comment here

Subscribe

Sign up to get our Newsletter delivered straight to your inbox

Privacy policy

Reviewed: 18 Mar 2014

This Privacy Policy governs the manner in which Human Factors International, Inc., an Iowa corporation (‚ÄúHFI‚ÄĚ) collects, uses, maintains and discloses information collected from users (each, a ‚ÄúUser‚ÄĚ) of its humanfactors.com website and any derivative or affiliated websites on which this Privacy Policy is posted (collectively, the ‚ÄúWebsite‚ÄĚ). HFI reserves the right, at its discretion, to change, modify, add or remove portions of this Privacy Policy at any time by posting such changes to this page. You understand that you have the affirmative obligation to check this Privacy Policy periodically for changes, and you hereby agree to periodically review this Privacy Policy for such changes. The continued use of the Website following the posting of changes to this Privacy Policy constitutes an acceptance of those changes.

Cookies

HFI may use ‚Äúcookies‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúweb beacons‚ÄĚ to track how Users use the Website. A cookie is a piece of software that a web server can store on Users‚Äô PCs and use to identify Users should they visit the Website again. Users may adjust their web browser software if they do not wish to accept cookies. To withdraw your consent after accepting a cookie, delete the cookie from your computer.

Privacy

HFI believes that every User should know how it utilizes the information collected from Users. The Website is not directed at children under 13 years of age, and HFI does not knowingly collect personally identifiable information from children under 13 years of age online. Please note that the Website may contain links to other websites. These linked sites may not be operated or controlled by HFI. HFI is not responsible for the privacy practices of these or any other websites, and you access these websites entirely at your own risk. HFI recommends that you review the privacy practices of any other websites that you choose to visit.

HFI is based, and this website is hosted, in the United States of America. If User is from the European Union or other regions of the world with laws governing data collection and use that may differ from U.S. law and User is registering an account on the Website, visiting the Website, purchasing products or services from HFI or the Website, or otherwise using the Website, please note that any personally identifiable information that User provides to HFI will be transferred to the United States. Any such personally identifiable information provided will be processed and stored in the United States by HFI or a service provider acting on its behalf. By providing your personally identifiable information, User hereby specifically and expressly consents to such transfer and processing and the uses and disclosures set forth herein.

In the course of its business, HFI may perform expert reviews, usability testing, and other consulting work where personal privacy is a concern. HFI believes in the importance of protecting personal information, and may use measures to provide this protection, including, but not limited to, using consent forms for participants or ‚Äúdummy‚ÄĚ test data.

The Information HFI Collects

Users browsing the Website without registering an account or affirmatively providing personally identifiable information to HFI do so anonymously. Otherwise, HFI may collect personally identifiable information from Users in a variety of ways. Personally identifiable information may include, without limitation, (i)contact data (such as a User’s name, mailing and e-mail addresses, and phone number); (ii)demographic data (such as a User’s zip code, age and income); (iii) financial information collected to process purchases made from HFI via the Website or otherwise (such as credit card, debit card or other payment information); (iv) other information requested during the account registration process; and (v) other information requested by our service vendors in order to provide their services. If a User communicates with HFI by e-mail or otherwise, posts messages to any forums, completes online forms, surveys or entries or otherwise interacts with or uses the features on the Website, any information provided in such communications may be collected by HFI. HFI may also collect information about how Users use the Website, for example, by tracking the number of unique views received by the pages of the Website, or the domains and IP addresses from which Users originate. While not all of the information that HFI collects from Users is personally identifiable, it may be associated with personally identifiable information that Users provide HFI through the Website or otherwise. HFI may provide ways that the User can opt out of receiving certain information from HFI. If the User opts out of certain services, User information may still be collected for those services to which the User elects to subscribe. For those elected services, this Privacy Policy will apply.

How HFI Uses Information

HFI may use personally identifiable information collected through the Website for the specific purposes for which the information was collected, to process purchases and sales of products or services offered via the Website if any, to contact Users regarding products and services offered by HFI, its parent, subsidiary and other related companies in order to otherwise to enhance Users’ experience with HFI. HFI may also use information collected through the Website for research regarding the effectiveness of the Website and the business planning, marketing, advertising and sales efforts of HFI. HFI does not sell any User information under any circumstances.

Disclosure of Information

HFI may disclose personally identifiable information collected from Users to its parent, subsidiary and other related companies to use the information for the purposes outlined above, as necessary to provide the services offered by HFI and to provide the Website itself, and for the specific purposes for which the information was collected. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information at the request of law enforcement or governmental agencies or in response to subpoenas, court orders or other legal process, to establish, protect or exercise HFI’s legal or other rights or to defend against a legal claim or as otherwise required or allowed by law. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information in order to protect the rights, property or safety of a User or any other person. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information to investigate or prevent a violation by User of any contractual or other relationship with HFI or the perpetration of any illegal or harmful activity. HFI may also disclose aggregate, anonymous data based on information collected from Users to investors and potential partners. Finally, HFI may disclose or transfer personally identifiable information collected from Users in connection with or in contemplation of a sale of its assets or business or a merger, consolidation or other reorganization of its business.

Personal Information as Provided by User

If a User includes such User’s personally identifiable information as part of the User posting to the Website, such information may be made available to any parties using the Website. HFI does not edit or otherwise remove such information from User information before it is posted on the Website. If a User does not wish to have such User’s personally identifiable information made available in this manner, such User must remove any such information before posting. HFI is not liable for any damages caused or incurred due to personally identifiable information made available in the foregoing manners. For example, a User posts on an HFI-administered forum would be considered Personal Information as provided by User and subject to the terms of this section.

Security of Information

Information about Users that is maintained on HFI’s systems or those of its service providers is protected using industry standard security measures. However, no security measures are perfect or impenetrable, and HFI cannot guarantee that the information submitted to, maintained on or transmitted from its systems will be completely secure. HFI is not responsible for the circumvention of any privacy settings or security measures relating to the Website by any Users or third parties.

Correcting, Updating, Accessing or Removing Personal Information

If a User’s personally identifiable information changes, or if a User no longer desires to receive non-account specific information from HFI, HFI will endeavor to provide a way to correct, update and/or remove that User’s previously-provided personal data. This can be done by emailing a request to HFI at hfi@humanfactors.com. Additionally, you may request access to the personally identifiable information as collected by HFI by sending a request to HFI as set forth above. Please note that in certain circumstances, HFI may not be able to completely remove a User’s information from its systems. For example, HFI may retain a User’s personal information for legitimate business purposes, if it may be necessary to prevent fraud or future abuse, for account recovery purposes, if required by law or as retained in HFI’s data backup systems or cached or archived pages. All retained personally identifiable information will continue to be subject to the terms of the Privacy Policy to which the User has previously agreed.

Contacting HFI

If you have any questions or comments about this Privacy Policy, you may contact HFI via any of the following methods:

Human Factors International, Inc.

PO Box 2020

1680 highway 1, STE 3600

Fairfield IA 52556

hfi@humanfactors.com

(800) 242-4480

Terms and Conditions for Public Training Courses

Reviewed: 18 Mar 2014

Cancellation of Course by HFI

HFI reserves the right to cancel any course up to 14 (fourteen) days prior to the first day of the course. Registrants will be promptly notified and will receive a full refund or be transferred to the equivalent class of their choice within a 12-month period. HFI is not responsible for travel expenses or any costs that may be incurred as a result of cancellations.

Cancellation of Course by Participants (All regions except India)

$100 processing fee if cancelling within two weeks of course start date.

Cancellation / Transfer by Participants (India)

4 Pack + Exam registration: Rs. 10,000 per participant processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the course (4 Pack-CUA/CXA) registration before three weeks from the course start date. No refund or carry forward of the course fees if cancelling or transferring the course registration within three weeks before the course start date.

Cancellation / Transfer by Participants (Online Courses)

$100 processing fee if cancelling within two weeks of course start date. No cancellations or refunds less than two weeks prior to the first course start date.

Individual Modules: Rs. 3,000 per participant ‚Äėper module‚Äô processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the course (any Individual HFI course) registration before three weeks from the course start date. No refund or carry forward of the course fees if cancelling or transferring the course registration within three weeks before the course start date.

Exam: Rs. 3,000 per participant processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the pre agreed CUA/CXA exam date before three weeks from the examination date. No refund or carry forward of the exam fees if requesting/cancelling or transferring the CUA/CXA exam within three weeks before the examination date.

No Recording Permitted

There will be no audio or video recording allowed in class. Students who have any disability that might affect their performance in this class are encouraged to speak with the instructor at the beginning of the class.

Course Materials Copyright

The course and training materials and all other handouts provided by HFI during the course are published, copyrighted works proprietary and owned exclusively by HFI. The course participant does not acquire title nor ownership rights in any of these materials. Further the course participant agrees not to reproduce, modify, and/or convert to electronic format (i.e., softcopy) any of the materials received from or provided by HFI. The materials provided in the class are for the sole use of the class participant. HFI does not provide the materials in electronic format to the participants in public or onsite courses.